The Failure-Frustration Cycle (FFC; The LearnWell Project 2018) always starts with students’ effort to succeed (Figure 1A) followed by their first failure or underperformance (Figure 1B). This initial disappointment is not exclusive to the FFC because this particular discrepancy between effort and results is inherent to students’ college life. Indeed, every student will encounter a time when their efforts will not yield the expected results on a test (formative or summative). However, following the first underperformance, student’s frustration (Figure 1C) can lead them to apply even more, but similar efforts toward learning (Figure 1D). Because these efforts are identical to the previous ones they will often result either in the same failure or in a marginal increase in performance compared to the efforts applied (Figure 1E). In fact, the main issue with the FFC is the lack of change from the student caught in the cycle applying similar type of learning techniques (aka efforts) over and over. Students are expecting different results simply due to the sheer amount of effort applied to the task. After the second iteration of underperforming, those students often develop anger (Figure 1F) toward the learning task, their teacher, themselves, or all of the above. Blinded or motivated by their anger, students proceed through the cycle once again (Figure 1G) exacerbating the underperforming outcomes at every cycle.

Not all underperformances lead students to enter the FFC. Following the lower than expected performance (Figure 1B), students can use the incurred frustration (Figure 1C) to critically self-reflect and correct or modify their learning process (depending if they failed to learn properly or applied the wrong learning techniques respectively). Consequently, students are not simply applying more efforts to the next task, but they are applying better efforts. On the other hand, changing the learning technique can yet lead to another iteration of underperformance qualifying for the FFC once again. Only if students successfully perform better following the change of learning technique would they steer away from the FFC.

Remarkably, the FFC seems to not only be caused by students’ lack of effective self-reflection, but also by students’ isolation. Undeniably, another way that students usually avoid the FFC vicious cycle is by regularly checking in with their instructor and/or fellow students following an underperformance. Teachers or fellow students are then able to point out to students errors in their ways dodging the incurred frustration (Figure 1C) or anger (Figure 1F) effectively breaking the FFC before it even takes place or at any iteration of the cycle. Noticeably, instructors themselves should be checking with their students to avoid FFC in their classroom (more on this below). Nonetheless, even teachers might not be able to rescue a failing student too deep into the FFC. Alternatively, institutions’ safe-guards against student failure and the FFC can be placed all along the semester. These safe-guards can include the community of concerns, learning management system’s targeted communications toward underperforming students, students’ advisers, etc. Finally and unfortunately, the most common way that students break the FFC is by dropping out of their course, major, or degree when too many underperformances (Figure 1B/E), frustration/anger (Figure 1C/F), or both accumulate through the cycle iterations. This ultimate failure of the educative system can be difficult to blame on one party or another since students, teachers, and institutions are involved in the FFC as detailed above. Nonetheless, in face of all those ways out of the FFC, numerous students every semester find themselves caught in the vicious cycle with little or no way out in sight.

Thankfully, teachers and institutions can rely on a wealth of research to support students through the FFC. First, understanding students’ metacognitive state when arriving and progressing through college is essential if educative teams want to detect students at risk of falling for the FFC. Even better, by considering a student’s position along the scheme of cognition and ethical development (Perry, Jr. 1981) we can match our instruction style to each student’s needs. Second, students experience teaching material differently based on their learning preferences that evolve through college. An essential basis to mitigating the effects of the FFC is to possess a good grasp on the necessary integration of learning styles through learning experiences in college. This integration is the only way toward students’ efficient learning and progress. Finally, I argue in favor of pairing our understanding of students’ cognitive development through college with the impact of learning styles integration on their educative journey through college to help students achieve the highest possible outcome during their college years.

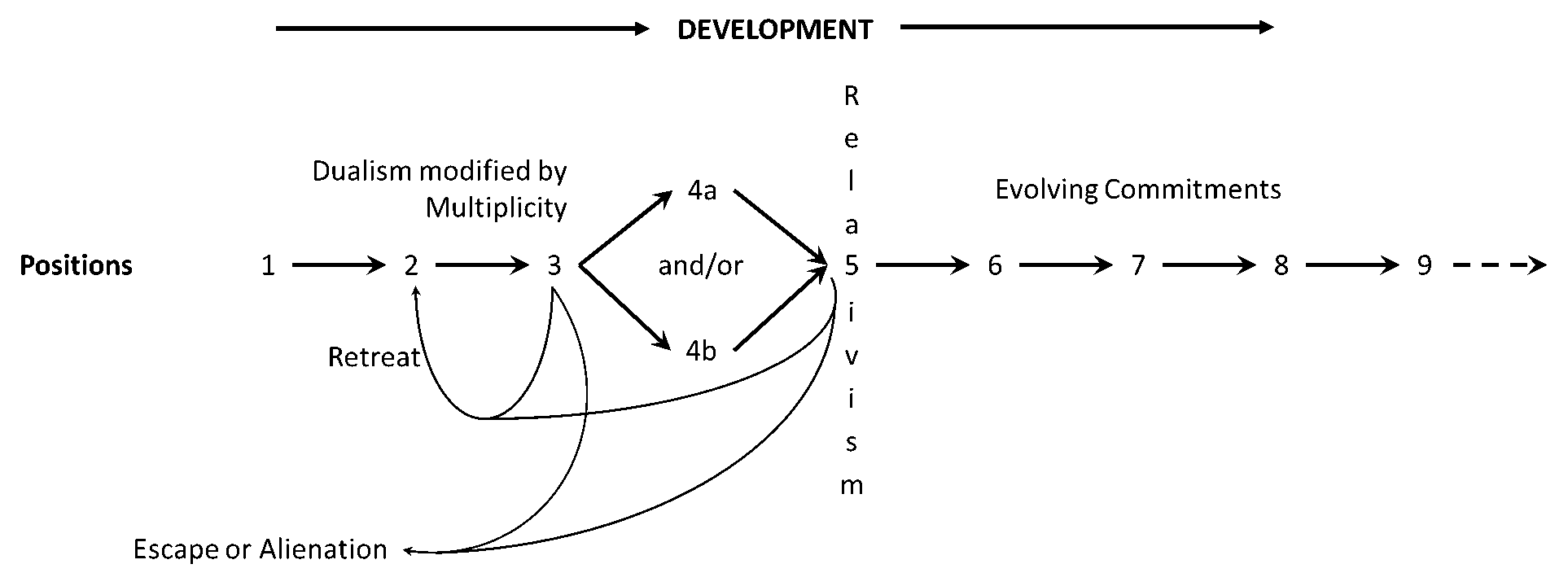

Figure 2: Map of development following Perry’s scheme of cognition and ethical development (modified from Figure 2 in Perry, Jr. 1981). Position 1 – Basic Duality. Position 2 – Multiplicity Prelegitimate. Position 3 – Multiplicity Legitimate but Subordinate. Position 4a – Multiplicity (Diversity and Uncertainty) Coordinate with the “known.” Position 4b – Relativism Subordinate. Position 5 – Relativism. Position 6 – Commitment Foreseen. Position 7 to 9 – Evolving Commitments. Retreat and Escape (or Alienation) can take place from position 3 or during the transition to position 5, both can be equated to iteration(s) of the FFC (more details in the text).

Perry’s scheme of cognition and ethical development lays out positions (or stages) and transitions representing students’ journey through higher education (Perry, Jr. 1981). With ten positions and nine transitions the journey is one of development and not of mere “phases,” hence this journey is linear and directional, each position encompassing the previous ones (Figure 2). Three main overarching developmental categories cover the scheme grouping positions along the students’ journey: Dualism, Relativism, and Commitment (Perry, Jr. 1981).

First, dualism is the idea that things are either this or that, good or bad, right or wrong. With dualism comes the belief that authority knows the answers and that a right answer always exists. This initial group of positions might be the most difficult of the three for students to progress through (see below). Second, relativism slowly develops from the belief that no right answer exists out there because everything is relative to everything but not equally valid. Lastly, Commitment (capitalized c) is the last group of positions covering the realization that committing decisions have to be made despite the acceptance of relativism allowing students to finally experience self-agency in their decision making (Perry, Jr. 1981).

Students’ journeys through dualism starts in position 1 (Figure 2) where they consider teachers as the depository of truth while students’ work is to accumulate this truth by following teachers’ directives compliantly. The first transition to the second position occurs mostly through peer interactions where other students question the authority of the all-knowing teacher and/or express diverse opinions. Moreover, authority might contradict itself leading students to realize that absolute truth does not exist or that authority can and should be challenged. Position 2 (Figure 2) finds students acknowledging diversity of opinion and truths, but by justifying this diversity they maintain the illusion that one true truth exists out there. For example, instructors might be poorly qualified or purposefully presenting diversity of truths as an exercise for students to find the absolute truth. During the second transition to the third position, students distribute fields of knowledge by their capacity to present one and unique truth to maintain the status-quo. Ultimately, this approach also fails when disciplines first classified as definite (e.g., the STEM disciplines) also fail to present one and unique truth. Students then reach position 3 (Figure 2) in which they finally acknowledge diversity as legitimate, but temporary. They believe the truth still exists out there, but cannot be found at the moment. In this way they justify a diversity of opinions without rejecting the idea of a single truth to each question. The next transition is complex and includes many different possibilities from moving forward to position 4a and/or 4b to retreat or escape (Figure 2). Those who oppose authority strongly will find refuge by retreating into the comfort of dualism (position 2; Figure 2) or by escaping the developmental stages altogether alienating themselves from their own education (Figure 2). In this case, retreat and escape are usually reached via the FFC due to students’ inability to transition further up on their developmental journeys.

From position 3, the path chosen depends on the attitude of students toward authority. Those who moderately oppose or adhere to authority will follow their respective path on the last step before relativism (positions 4a and 4b respectively; Figure 2). Indeed, students moderately opposing authority go on to maintain dualism in face of uncertainty by dividing things in two categories: one for which authority has the right answer and one for which authority does not know, thus, where every opinion is valid (position 4a; Figure 2). In this position students still assess people through their thoughts/ideas and successfully account for multiplicity of opinions while recognizing authority’s judgement. The greatest challenge is waiting for them in their transition into relativism because at this stage students believe they have already found relativism. On the other hand, students trusting authority let go of dualism and set themselves up for discovering relativism through the lens provided by the authority (position 4b; Figure 2). Changing perception from accomplishing what is asked of them to thinking how they are asked to think to accomplish their task allows students to have a foot in the door of relativism in position 4b (Figure 2). Here, students discover the powerful process of forging their own opinion by weighing facts through independent thinking. However, this stage is also setting up a great challenge since students still have to realize that even authority’s knowledge can be challenged when developing one’s own personal opinion based on facts. Interestingly, students can transition from position 4a to 4b before going on to position 5 easing up the entry into relativism.

The transition to position 5 (Figure 2) starts from the stage at which students accept what the authority wants them to do as depending on the simplicity of the task, only applying independent thinking where no right answer exist yet. Then, students’ journeys take them to the realization that no task is simple, but all simple tasks rely on complex assumptions and critical thinking already accomplished by others before them. Position 5 (Figure 2) leaves students painfully aware of the important necessity of prior knowledge for them to assess opinions in each and every field they study. Only independent thinking based on known facts can assess ideas from other or oneself; however, students remain sheltered from committing to one opinion or another due to the sheer amount of knowledge they perceive they need to learn first. Alternatively, students here again can withdraw to retreat toward dualism (position 2; Figure 2) or escape. Retreat and escape are usually reached after iteration(s) of the FFC once again illustrating students’ struggles on their developmental journeys.

Once relativism has settled, students are slowly realizing that they need a way to deal with the sea of opinions and knowledge available to them. Students acknowledge that they will need to choose, to commit to some interests and miss out on other interests (position 6; Figure 2). This stage can be very stressful for students since the human nature is to fear missing out (Fear Of Missing Out or FOMO; Przybylski et al. 2013); nonetheless, the way forward is by Committing (as opposed to lowercase unquestioned commitments of the past; Perry, Jr. 1981) focusing on what drives one to action and this can only be done from within oneself. Further positions are the stages at which students commit to their first choice (position 7; Figure 2), then realize they will have to balance each commitment with the old ones constantly stretching their inner self to accommodate their choices while facing the consequences of said choices (positions 8, 9, and further; Figure 2). The further students go the more they realize that prior commitments are not set in stone while new commitments might call for a balancing, ranking, or even changing act of all commitments. Interestingly, although this developmental scheme is presented along two axes, it appears that the process of cognition and ethical development is repeated throughout one’s life with the added knowledge accumulated from previous iteration(s) (Perry, Jr. 1981; see below).

The art of guiding students through their cognitive development voyage is one that teachers have to excel at while managing to address the diversity of students’ stages. Not all students arrive in college at the same position in the scheme of cognition and ethical development (Perry, Jr. 1981). The challenging situation faced by teachers in front of freshman classes of hundreds of students is not hopeless. Indeed, the first step in addressing students’ needs and providing an environment allowing them to steer away from the FFC is to understand “students’ way of making meaning” (Perry, Jr. 1981). This developmental scheme gives us the vocabulary to recognize and address each student’s needs (more on concrete actions below). The real challenge resides in finding a way forward for students’ transitions through the scheme. A fruitful avenue is one of the human growth process developed in the experiential learning theory of growth and development (Kolb 1981). Relying on the recognition of four different learning styles, this theory gives us the tools to help students along their cognitive development journey and away from the FFC.

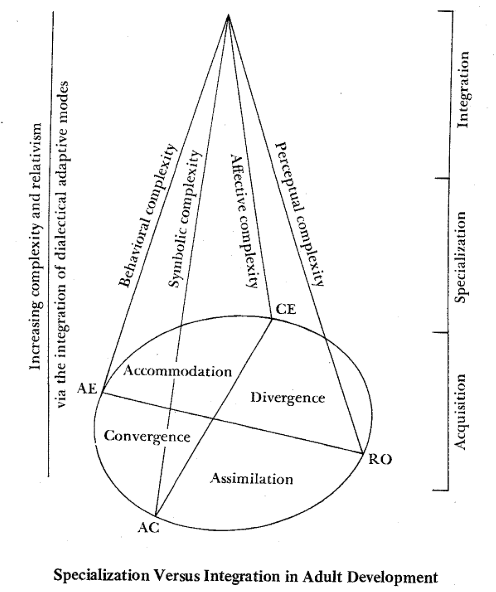

Figure 3: Experiential Learning Model (modified from Figure 1 in Kolb 1981). Learners start from experiences (1) leading to reflections (2) then to generalization (3). Finally, learners test those concepts in new situations (4) creating new experiences, thus, continuing the cycle. The required abilities to navigate the cycles lie along two axes (see text for details): Concrete Experience (CE) ↔ Abstract Conceptualization (AC), and Active Experimentation (AE) ↔ Reflective Observation (RO). Four learning styles account for the areas delimited by the ability axes: Accommodation, Divergence, Assimilation, and Convergence (see text for details).

The Experiential Learning Model (ELM; Kolb 1981) posits that learning takes place through a series of experiences (Figure 3, 1) that are observed and reflected upon (Figure 3, 2). In turn, those observations and reflections allow the creation of theory (Figure 3, 3) that will be tested (Figure 3, 4), thus, creating new experiences and continuing the cycle. Four main abilities are needed to go through iterations of the ELM cycle: Concrete Experience (CE), Reflective Observation (RO), Abstract Conceptualization (AC), and Active Experimentation (AE). Evidently, those abilities each lie at the extreme of two continuums, CE ↔ AC and AE ↔ RO (Figure 3). On one hand, learners can initially either be completely absorbed in new experiences (CE) or they can take some steps back from experiencing to allow them to create theories from observations (AC). On the other hand, learners can initially either use theories to solve problems or make decisions (AE), or they can spend time reflecting on their observation taking different point of views in the process (RO). These two axes create a two dimensional plan characterized by four spaces representing four distinct learning styles (Figure 3; Kolb 1981).

Accommodator(CE & AE; Figure 3) are the doers, they take risks and can usually intuitively adapt even when theories do not hold up in face of new situations. Divergers(CE & RO; Figure 3) are best when exploring new situations from different perspectives (i.e., brainstorming). They are generating ideas based on their current experience and are able to explore all avenues of a given problem. Assimilators(AC & RO; Figure 3) are also able to take different perspectives to a same problem. However, they focus on extracting patterns and theories with the intent to precisely explain a given phenomenon being content with staying in the theoretical realm. Convergers (AC & AE; Figure 3) are brilliant at focusing their knowledge on specific problems to reach a single correct answer. Pragmatic, they shine when extracting needed information to narrow their thought process toward a solution. Initially potentially mutually exclusive, the abilities at the end of the two axes (CE ↔ AC and AE ↔ RO) are nonetheless necessary to progress along and through iterations of the ELM cycle. Thus, learners slowly develop those abilities through cycle iterations; yet, not all abilities are developed equally at each new cycle and some of the cycles see the learner regress along one or more ability axes, thus in one or more learning styles. Those regressions can lead to iteration(s) of the FFC and present important pitfalls in students’ development journeys. Nonetheless, these movements along the two ability axes and among the four different learning styles through the repeated ELM cycles lead the learners along the third dimension of learning, the human growth process (Figure 4; Kolb 1981).

Figure 4: The Experiential Learning Theory of Growth and Development illustrating the human growth process (Figure 5 in Kolb 1981). The two abilities axes are represented at the bottom of the cone (Concrete Experience ↔ Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation ↔ Reflective Observation) as well as the four learning styles (Accommodation, Divergence, Assimilation, and Convergence). The stages of the human growth process are represented on the third axis, vertically: acquisition, specialization, and integration (see text for details).

The experiential learning theory of growth and development presents learning as a life-long succession of ELM cycles with the ability axes and learning styles along a third dimension of human growth process (Figure 4; Kolb 1981). This theory accounts for the tensions created between the four learning styles while learners grow through the three stages of the human growth process. The first stage, acquisition, starts at birth and continues until adolescence (Figure 4) and represent the gain of mental edifice necessary for learning. Specialization, the second stage, spans from education to initial life and work experiences (Figure 4) and usually focuses on one specific learning style developed through social and educational forces. Finally, integration, the third stage (Figure 4), extends beyond the mid-career to the end of life during which learners develop fine-tuned and specialized skills integrating the four learning styles together. Interestingly, along the three stages of the human growth process, relativism and complexity steadily increase by progressively resolving the tensions between the four learning styles and abilities (Figure 4). Although one learning style and the corresponding abilities can initially develop relatively independently, the four learning styles and abilities need to be integrated in order to reach true creativity and growth (Kolb 1981). This integration takes place during the critical stage of specialization, which climaxes during learners’ college years. The FFC present a major danger to the adequate integration of the four learning styles during students’ developmental journeys; thankfully, instructors are not defenseless when facing the FFC in their students (more practical details below). The juxtaposition of the experiential learning theory of growth and development, the human growth process, and Perry’s scheme of cognition and ethical development sheds light on students’ learning journey in new and unexpected ways. Obviously, the FFC can take place if the nature of the efforts applied by students (Figure 1A & D) is incompatible with the learning taking place at that particular moment. A student transitioning away from positions 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 2) needs to learn how to weigh different opinions against the correct answer (position 4a or 4b; Figure 2) and/or against each other in search of the truth (position 5; Figure 2). In this case, if the students maintain the same type of efforts allowing them to obtain successful grades in the past (e.g., rote memorization) they will only underperform at those new tasks (e.g., evaluating evidences) regardless of the amount of efforts applied (Figure 1E). Furthermore, the nature of the assessment students take can also play a role in entering or continuing the FFC during the frustration and anger phases (Figure 1C & F). An assessment predominantly requiring or favoring one learning style is bound to be an obstacle for students lacking a good grasp of this particular learning style at this moment; thus, leading those students to underperform despite their capacity to learn effectively at this stage. For example, an instructor spent several lecture sessions on one subject and used a lot of formative assessments requiring students to apply the presented theory to solve problems. Since most of the students performed above average on the formative assessments, the instructor felt confident when assigning the majority of the midterm exam on this particular subject. However, the midterm exam consists of a reflective open-ended question where students are asked to explore different perspectives and present them in a coherent manner exposing qualities/flaws in the prompt. Then, the instructor is perplexed when half of their top 20% students failed to score more than a 70% on this midterm exam. Here, there was a major discrepancy between the formative assessments, developing students’ Active Experimentation abilities (AE; Figure 3), and the midterm exam, testing their Reflective Observation abilities (RO; Figure 3). Therefore, students underperforming in these ways will understandably develop frustration and/or anger (Figure 1C & F) not understanding why they could not perform as expected after they successfully performed during the formative assessments prior to the midterm exam. Evidently, those two examples reveal mechanisms of entry or maintenance of the FFC (using the scheme of cognition and ethical development and the experiential learning theory of growth and development respectively) were voluntarily extreme by nature. On one hand, students applied inappropriate efforts to the task at hand without their instructor noticing the discrepancy; on the other hand, students are taught in one specific way and tested in a completely different way. Nonetheless, by highlighting the extremes, these examples illustrate the spectrum of incongruities existing between students’ stage of cognition and ethical development and the tasks required by teachers or between students’ learning and testing as defined by their instructors.

Interestingly, juxtaposing those three theories (experiential learning theory of growth and development, human growth process, and Perry’s scheme of cognition and ethical development) allow us to define new ways of developing our courses and/or testing students. This body of theories begs instructors to assess their students’ position along the scheme of cognition and ethical development (Figure 2) ahead of time, usually at the start of the semester. This type of assessment can be easily done via informal surveys, inventories (e.g., Learning and Study Strategies Inventory; Weinstein and Schulte 1987), or classroom technique assessments (Angelo and Cross 1993) at the start of the semester. For example, instructors should not assume their students completely understood prior courses content and concepts. Instead, instructors should use assessments such as pre-class surveys/inventories or first class test (only graded for participation of course). In the former students are asked to fill a survey before the semester start in which they state their understanding of key content and concepts; whereas, in the latter students are tested on key content and concepts on the first day of class. Although the first option relies on students’ self-assessment capacities as well as honesty, the second option can be alienating to students if not presented appropriately (e.g., graded for performance or hidden from students until the first class starts). Finally, even if implementing such assessments requires additional time and logistic, the reward for doing so largely outweighed the costs when compared to a semester of struggles for students failing to succeed and frustration for instructors failing to reach their students in their classes.

The objective of those techniques is to minimize students’ underperformance, frustration, and anger (Figure 1B, C, and F respectively). Only when instructors have a good idea of where their students stand along the scheme would they be able to help students along their developmental journey efficiently. Furthermore, instructors should pay close attention to matching formative and summative assessments along the semester in order to prevent underperformance surprises as we have seen above. Alternatively or concomitantly, instructors should provide a variety of assessments (formative and summative) to give an opportunity for the four abilities and/or the four learning styles (Figure 3) to shine. Likewise, instructors need to keep in mind the ELM structure of learning through experience when designing their classes (Figure 3). By designing lessons incorporating at least two (due to their adjacent nature) or all stages of the learning cycle (concrete experience – Figure 3, 1 – observations and reflections – Figure 3, 2 – formation of abstract concepts and generalizations – Figure 3, 3 – testing implications of concepts in new situation – Figure 3, 4), instructors assure all students a chance to progress along their own human growth process (Figure 4). Finally, the objective of college education is to guide each and every student from dualism to relativism (Figure 2) through specialization (Figure 4) to give them the best tools and abilities for reaching integration in their future work (Figure 4). Of course, students do not all start or finish their college journey at the same stage of development rendering this task even more difficult for instructors. Nevertheless, we cannot achieve that ambitious goal by providing a generalized education hoping for most of the students to find their own way through college while maybe learning a thing or two. In other words, students are not pepper grains going through the mill of college. We need to be very purposeful and directed in our intentions when designing classes, majors, and the curriculum in general using a combination of backward design with the objective of changing college from a pepper mill to a series of sieves meant to help students find their way through their education.

Figure 5: Backward Design stages (Wiggins and McTighe 2005). By focusing on “Content and understanding” (Stage 1), instructors can choose efficient ways to test this understanding in students (“What is assessed,” Stage 2), then, choose how to teach this content (“What is taught,” Stage 3).

Arguably, most of the students in the FFC are falling into the vicious cycle due to poor class design by instructors. Too often instructors start their classroom design based only on the content that they desire to teach and cover. However, the content should not be the focus of classroom design, but the last step in our classroom design (Wiggins and McTighe 2005). Indeed, instructors first need to focus on desired results (Figure 5, Stage 1), then on assessment (Figure 5, Stage 2), finally on teaching content (Figure 5, Stage 3). Backward design is counterintuitive, or backward, because we believe assessment can only be designed after the content was established. However, this relegates learning outcomes on the side and discards their importance in lesson planning and design. By first focusing on learning outcomes we insure a purposeful and focused learning experience for students in our classes. The first stage of backward design requires instructors to focus on the desired outcome for students. What do we want students to be able to do with what they are going to learn in this class? Such question should guide instructor design at this stage. Because content will always necessitate more time that instructors have for students to learn, it is important for the former to focus on what the latter need to make sense of the content. After all, teaching is about equipping students with the right tools and abilities to use and transfer their learning (Wiggins and McTighe 2005). The second stage of backward design requires instructors to pause before thinking about teaching content. What evidence will we accept for effective learning transfer by students? Here, the alignment between desired outcome(s) from stage 1 and assessment in stage 2 is essential. Importantly, instructors should not shy away from testing some outcomes because of their difficulty to assess. Moreover, assessments need to be wholesome and test all facets of students understanding (i.e., explain, interpret, apply, perspective, empathy, and self-knowledge; see Wiggins and McTighe 2005 for more details) and abilities (Concrete Experience, Abstract Conceptualization, Active Experimentation, and Reflective Observation; Figure 3). Finally, the third stage of backward design requires instructors to teach for understanding focusing on learning transfer, meaning making, and acquisition (Wiggins and McTighe 2005). How will we support and prepare learners for their future autonomous learning? Understanding cannot simply be told, instructors need to support students as they actively construct meaning. This last stage is where instructors think about teaching content; however, they do so with informed intent based on learning objective (stage 1; Figure 5) and assessment (stage 2; Figure 5).

Backward design considers content as a resource instead of an objective. Content is a mean to an end and this end is students learning. Consequentially, an instructor should not be considered as sage on the stage anymore, teaching for the sake of teaching, but a guide on the side (King 1993), insuring meaning making and learning transfer by the learner. Undeniably, instructors are not the depository of knowledge anymore; textbooks first, then Google took that role from them. Backward design gives the opportunity for instructors to once again gain agency over students learning and steer away from the dictatorship of content over learning. By doing so, instructors build the very first step toward avoiding the FFC due to the intentionality and clarity of their course structure providing much needed support to their students.

Although the FFC is pervasive (Figure 1), students need not fall prey to the vicious cycle since instructors can act both proactively as well as while students struggle with the FFC to prevent or simply break the cycle. Certainly, we have seen the importance of understanding where students are in their cognition and ethical development for understanding students’ needs in term of learning (Figure 2). Nonetheless, knowing student struggles is different from helping students through their struggles. That is why considerations of the ELM (Figure 3) are essential in order to provide the necessary help students need to go through the specialization phase of their human growth process (Figure 4). Finally, backward design (Figure 5) provides the framework in which instructors can efficiently implement the steps that each students will need to progress along their educative journey and minimize the pitfalls potentially leading to the FFC. Here I have only presented the guiding directions for effective classroom planning/design. However, lots of other factors should be taken into consideration if instructors find themselves failing to support some students. For example, beyond the scope of this paper were the fields of educative theory exploring the reasons behind student resistance (Tolman and Kremling 2016), information overload (Johnson 2016; Ruff 2002), and cognitive load theory (Hultberg et al. 2018). These fields are not alternative to those presented here; nonetheless, they can provide useful insights for further roadblocks encountered by instructors who already understood and implemented the concepts described in this paper or those mentioned just above. Finally, one last area of expertise instructors will want to explore since our student body becomes more and more diverse is the research on cultural competency in the classroom (Tanner and Allen 2007) and adaptive learning (Newman et al. 2016). It is my intention that after understanding and implementing the models describe in this paper instructors will be well equipped to dive into these specialized areas of teaching competency in the 21st century classroom. As teachers, our objective is to provide our expertise to all students coming into our classrooms. Evidently, some students will still fail to progress through higher education, but this fact should not discourage us from reaching out to each and every student with help and advice. Passionate educators strive to help all of their students to find the keys to their own success.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my peers from the EPE 672 class for a semester full of insightful discussions and eye opening discoveries. Many thanks to Dr. Jeff Bieber for brilliantly leading this class and providing guidance to all of us on our debuts through higher education. I am sure the journey is still long and windy, but worth it. Additionally, I would like to extend a forever thank you to my wife, Jacqueline Dillard, with whom I always discuss my questioning at length and who walks the path of life alongside with me, I love you deeply. Finally, special thanks to Zoe Dapore and Makayla Dean, two undergraduate students who are working with me on my research and who provided vital insights during the composition of this essay.

Reference list

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. Jossey-Bass.

Hultberg, P., Santandreu Calonge, D., & Safiullin Lee, A. E. (2018). Promoting Long-lasting Learning Through Instructional Design. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 18(3), 26–43. doi:10.14434/josotl.v18i3.23179

Johnson, B. A. (2016). Helping Students Overcome Information Overload. AdjunctNation.com. https://www.adjunctnation.com/2011/06/01/helping-students-overcome-information-overload/

King, A. (1993). From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30–35. doi:10.1080/87567555.1993.9926781

Kolb, D. A. (1981). Learning Styles and Disciplinary Differences. In A. W. Chickering (Ed.), The Modern American College (pp. 232–255). San Francisco, California: JosseyBas. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00221340008978967

Newman, A., Bryant, G., Fleming, B., & Sarkisian, L. (2016). Learning To Adapt 2.0: the Evolution of Adaptive Learning in Higher Education Table of Contents. http://tytonpartners.com/tyton-wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/yton-Partners-Learning-to-Adapt-2.0-FINAL.pdf

Perry, Jr., W. G. (1981). Cognitive and ethical growth: The making of meaning. (A. W. Chickering, Ed.) The modern American college. San Francisco, California: Josev Bass.

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Ruff, J. (2002). Information overload: causes, symptoms and solutions. Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Learning Innovations Laboratory (LILA). http://workplacepsychology.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/information_overload_causes_symptoms_and_solutions_ruff.pdf

Tanner, K., & Allen, D. (2007, December). Cultural competence in the college biology classroom. CBE Life Sciences Education. doi:10.1187/cbe.07-09-0086

The LearnWell Project. (2018). Help Students Avoid the Failure-Frustration Cycle. https://www.thelearnwellprojects.com/thewell/help-students-avoid-the-failure-frustration-cycle/. Accessed 9 October 2018

Tolman, A., & Kremling, J. (2016). Why Students Resist Learning: A Practical Model for Understanding and Helping Students (Reprint ed.). Stylus Publishing. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Students-Resist-Learning-Understanding/dp/1620363445

Weinstein, C. E., & Schulte, A. C. (1987). Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI). H&H Publishing. doi:10.1080/19443994.2015.1042068

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (Expended 2.). Alexandria, Virginia USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.