This blog post was inspired by the reading of an old Change article, from 1995, From Teaching to Learning a New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education (opens in a new window). To be clear, the structure of this post is following the structure of the article at first. I aim to provide a condensed version of the article and then discuss its merits in light of where we are nowadays in higher education.

Mission and Purposes

Well, there is nowhere best to start than with this quote that I wholeheartedly agree with: “A college is an institution that exists to produce learning.” Based on that, which I believe is on the nose, the article makes three first and important constatations:

Wanting more output without adding more resources/money is not gonna work. For example, more students per teacher is not going to yield better graduation rates.

Teachers generally agree and will defend the statement above with all their heart. However, it does not follow that they will work from that perspective in their classroom. For example, many of us still lecture for their entire class time.

Working from within the (still, since 1995) current paradigm (teachers hold the knowledge and students’ brains are receptacles to be filled with it) will not be successful in increasing student success or learning. Increasing learning would be possible only if we shift to the (still since 1995) new paradigm.

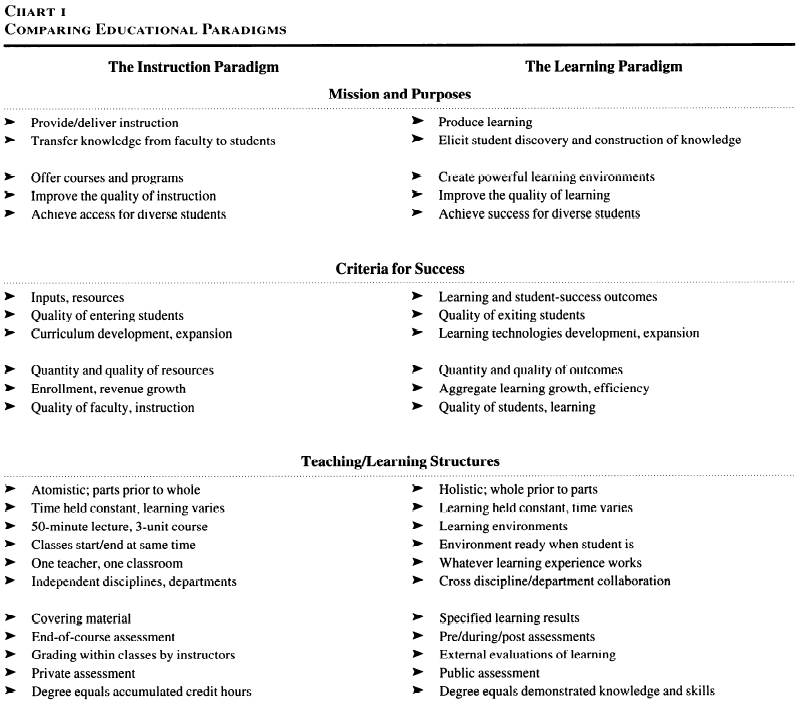

Shifting the paradigm in this instance does not mean a complete 100% shift: nothing of the old and everything is new! Let’s set the scene first: the somewhat old paradigm is that colleges’ mission is to teach, to produce instruction (see the left side of the chart 1 below); whereas, the somewhat new paradigm is the quote above (colleges’ mission is to produce learning; see the right side of the chart 1 below). The authors chose the term “produce” with care. They didn’t say provide, support, or encourage for a very specific reason: responsibility. When colleges said that their goal is to produce teaching that’s how they assess if they met their objective: how much teaching did they do. For example, an automotive assembly plant aims at producing cars, not selling them. So that’s exactly how they assess if they meet their objective (how many cars were produced). Let the dealerships worry about sales. In case you missed it, the analogy here is that automotive assembly plants are teachers and the dealerships are the students: Teachers produce teaching, let the students worry about learning.

First chart from the article linked on top of this blog post. Continued in the next image.

Criteria for Success

Careful now, taking responsibility does not mean making sure results follow or taking full control of the journey. It is merely a way to define the goals and actions that will be undertaken to achieve said goals. Furthermore, it is a way to set the criteria that will be used to measure success. Responsibility is not a zero-sum game where if it is taken on by the colleges and teachers, then, students don’t have any responsibility in their learning. Students already define their own success and how they measure it, do not worry about them giving up on their learning because we, the colleges and teachers, said it was our responsibility too. It is well understood by all and every students that they are responsible for learning. It seems that colleges and teachers are the one refusing to take responsibility in this game. We support students, provide learning opportunities, allow access to … we know what good does access do to minority students if they don’t have the tools to learn!! No, it’s time for colleges and teachers to put their money where their mouth is: let’s take responsibility, alongside students, for their learning.

Therefore, when it comes to measuring success, solely measuring inputs ignores the most important thing, outputs. Of course, meaningful outcomes need to be measured. Nevertheless, using the same analogy as the article’s authors: Would you not agree that funding a college on the number of math problems solved by students, although a silly measure, makes more sense than on the number of students in the math classrooms?!

Teaching/Learning Structures

The authors’ discussion of structures is deeply interesting as well as troubling when hindsight is 2020 (see what I did here?! We are in 2020 so it’s fitting :-p).

Interesting because colleges are atomistic structures similar to the Life’s classification I teach every semester: One teacher and a bunch of students in a room equals a classroom; Several classrooms together equals a building; Several buildings together equals a program/division; etc. The problem with that structure is that emergent properties (aka learning) are almost killed right of the bat! A college is nothing but the sum of its parts and its objectives are nothing but getting more of those parts together year after year …

Troubling because not a lot has changed over time. We are still under the tyranny of time even when faced with study after study showing that each person learns differently. We still force everybody (differently shaped pegs) through the same schedule. It is mind boggling that when students’ lack of preparedness is identified, we develop a new course to do just that instead of thinking about embedding preparedness in all classrooms! Even more mind boggling is the advancement of critical thinking courses … this is opposed to the very idea of critical thinking!!

To this day, we have departments fighting each others for funding as part of the same college based on input (how many students they attract) rather than colleges competing with each others based on output (how much their students learn). I can go on, but let’s go back to the article at hand with a perfect analogy: currently, degree represent the amount of time students invested in their learning rather than the amount of skills they learn during their learning.

Continued from the previous image.

Learning Theory

In the teaching paradigm, individual students learn individually and are tested individually on their learning. This very idea cultivates a view of life as a win-lose situation where success is an individual feat. On the other hand, the learning paradigm develops learning environments where life is a win-win situation. Collaboration, teamwork, and group efforts leads to learning and assessments reflect that fact (at least partially). Even when seemingly learning for themselves (after all what one student learns is in that students’ head), students still worked in a shared learning environment, thus, participated in other students’ learning.

Productivity/Funding

The article’s authors mentioned already in 1995 that no definition/standard for colleges’ productivity under the learning paradigm: “cost per unit of learning per student.” They also added that there might be no need for defining such standard, we only need to use it and keep its definition varied and changing other time rather than single and fixed. We do have a definition/standard for colleges’ productivity under the teaching paradigm: “cost per hour of instruction per student.“ This definition has driven colleges to drastically diminish learning by increasing productivity simply because they don’t assess the former while misdefining the latter.

We’re wasting everybody’s time because of how we fund colleges. It does not matter how many students leave the college without learning a thing or without a degree. What matters is only that enrollment remains constant or increases on a semester-to-semester basis. Colleges measure the graduating rates in two/four/six years … have you looked at those numbers?! They are abysmal and terrifying. Yet, lip-service is done to improving them year after year while funding remains anchored on butts in seats.

https://cdn.business2community.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Mistis-Blog-Image-3.jpg

What’s next?

In my opinion, reducing the entire higher-education to a single block and describing what is done in term of teaching, learning, administration, etc. is a little bit fast and loose for me. In fact, I suspect that teachers behave vastly differently depending of where they teach and so do students. There, it becomes an intricate game of deciphering what causes what since inputs, paradigms (teaching or learning), and outcomes (meaningful or not) vary at the same time. Furthermore, this blog post is long enough without diving into that today.

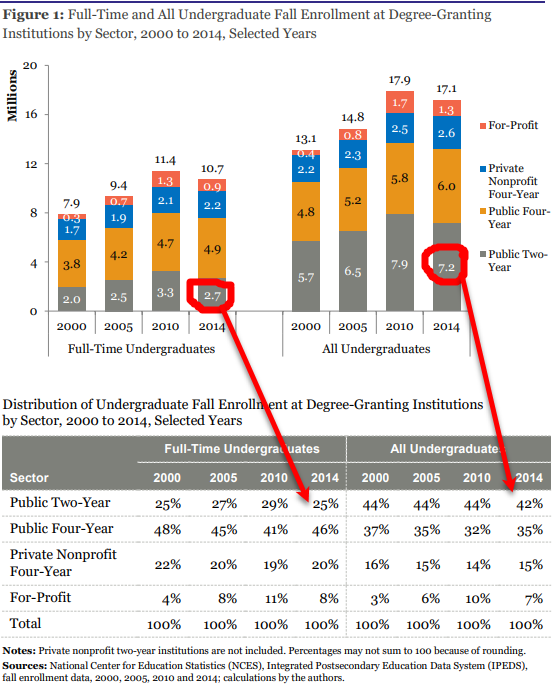

Nonetheless, I will share some insights here. Turns out, in 2014 in the USA, 42% of all and 25% of full-time undergraduate students where enrolled at a community college (public two-year in the figure below). That has to count for something when we try to assess our higher-education system without accounting for its diversity, don’t you thing?! Finally, maybe we shouldn’t trust community college low graduation rates for a slew of reasons as this article explains (opens in a new window). If you learned anything in this blog post above, maybe reading the (short) comment section of the last article I shared just before will enlighten you as to what a teaching paradigm does to our vision of education.

[plain text URL: https://www.communitycollegereview.com/blog/the-catch-22-of-community-college-graduation-rates]

Figure 1 of the “Trends in Community Colleges: Enrollment, Prices, Student Debt, and Completion” report published in 2014 (opens in a new window). This report contains a slew of data to dive into and extract the substantific marrow as we say back where I come from!

[plain text URL: https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf]

![This picture comes from a colleague’s excellent blog post (opens in a new window) and illustrate one of the points I make below perfectly. [plain text URL: https://educationrickshaw.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/t-11.png]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/598782f4be6594b05b3cb7bf/1604076226390-NPRBNHS434S204JLNGNL/2020_10_30+Teaching+to+Learning+Paradigm+shift.png)